#yet another Grant Wilson character study

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I have to analyze a multimedia project (in the form of another multimedia project) for a class… Should I do the most embarrassing thing ever or

#I don’t think podcasts (with no accompanying visuals) count as multimedia?#but idek what I would want to analyze about DnDads anyway#yet another Grant Wilson character study? 😭😭 LMAO#and then I thought#HOMESTUCK#but no I don’t even care enough about Homestuck anymore to analyze anything about it#and THENNN I thought.#danganronpa#💀💀 goddd#I know EXACTLY what I would analyze too#<- the fuckin transmisogyny of Shinguuji’s whole character (and also other characters)#Shinguuji was my favorite character since I was like 14 LOL nobody gets him like I do fr 😤 /lh#anyway I could do a zine and put red lipstick all over it. awesome#ahem anyway. sorry I’ll never post about dr again (lie) (it’s my worst ever special interest forever) (but only like 5 of the characters)#(and I don’t even like it anymore I just really like criticizing it. it’s fun)#OKAY I’M. DONE. SORRY#😇😇 teehee#I need to stop saying teehee all the time#chalcy stuff#EDIT: just reread these tags… awful awful awful. hs and dr in one post in 2024. nightmare

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An essay on regrets, of which I've had too many.

I spend a lot of time – perhaps too much time – thinking about mistakes I’ve made in my life. The honest mistakes I can forgive; it’s the mistakes of character than I cannot let go.

The earliest one I can remember – and the one that gnaws at my conscience the most – occurred in elementary school. I was walking down a hallway with a friend when Beth, a gangly, freckled redhead with a short bob haircut, was walking towards us. My friend started called Beth “Godzilla” and pressed himself against the wall as he passed her. Me, being a total jackass, did the same. Later in class, our teacher said that Beth was in the office, crying. She told us about how it was tough for Beth because her mother had passed, that she and her dad were just getting by, that Beth often had to make her own clothes. I’ve been walking on this planet more years than I care to reveal, and I can tell you without a doubt I never felt so small in my life.

Looking back at this episode I’m appalled at my gall to judge someone else’s beauty. Who the hell am I? Cary Grant? Brad Pitt? Oh, hell no. I’m reminded of the lyric from the Sparks song Johnny Delusional: “Some might find me borderline attractive from afar

But afar is not where I can stay and there you are.”

Is being thick headed at times a character flaw? Surely a lack of courage is, and also, I think, not being in tune with those around you. My next big regret was not being alert to the feelings of a girl, Samantha Wilson, in junior high school. We sat together in the back of math class, talking when the teacher wasn’t looking, passing notes, having a laugh, and, occasionally, I’d help her with math problems. What I didn’t notice, and didn’t realize until decades later, was that she “liked” me in that junior high school way of early romance. I liked her too but was too afraid to say anything. And so we sat, side by side, each in a state of what we thought was unrequited love.

I have many other regrets – not studying harder (or at all) in school, taking way too long to finally go to college, not asking the Army recruiter about journalism jobs (picking military police instead, leading to yet another regret – being a terrible MP), and, well, too many others to mention.

So many cases of “would’ve, could’ve, should’ve,” what comedian Gary Gulman calls the Holy Trinity of Regret.

So, what to do with all of this regret? Well, I’m trying to do what pro football players do after losing a game – look at the film, analyze the mistakes, and try not to repeat them.

When we first see a person, all of us make snap judgments regarding their physical appearance. We make judgments about their looks, whether they appear to be someone of means – in short, whether they would be a good mate (in the reproductive sense of the word). That’s buried in our genetic code. But after that quick evaluation, we need to look deeper, or at least I do. You might be doing that already, being of better character than me. The world is rich in differences of appearance, and I should try to marvel at that, rather than being a boorish judge of looks.

As a professional wordsmith, I need to remember that words are powerful tools that should build someone up, rather being used as a weapon of thoughtless, cruel abuse. I am a craftsman of words and, if I may paraphrase Stan Lee’s Spiderman, with great power comes great responsibility.

In short, I’m trying – perhaps not always succeeding – to be a better person.

I’m also trying to be thankful of where this meandering path through life has led me. I’m in a very happy place. I have a wife whom I adore – which I will tell to anyone who stands still long enough for me to do so. The two of us have three lovely daughters and six great grandchildren. Despite all the regrets, would I change anything that could result in losing that? No, of course not.

For my family and friends, perhaps I should embrace the Edith Piaf song “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien.”

Non, je ne regrette rien (no, I regret nothing)

Car ma vie, car mes joies (because my life, because my joy)

Aujourd’hui ca commence avec toi (today it begins with you)

For your listening pleasure, Edith Piaf and Sparks

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ixdvm8-MdUs

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rCxLpte5loY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v5jtqCo43WM

#Regret #Sparks #EdithPiaf #kindness

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Inside Marvel’s ‘Loki’: Sorcery, Time Travel, and a Mystery Villain!

For a roughly 3,000-year-old god, Loki sure isn’t showing his age. In the trippy six-episode Disney+ series that bears his name, he’s full of his usual maniacal vigor and charm, and no wonder: This time, Tom Hiddleston’s god of mischief — first introduced in 2011’s big-screen Thor as the troublemaker, shapeshifting brother of Chris Hemsworth’s god of thunder — takes center stage.

Loki, a time-traveling procedural drama, opens up the complex character in ways fans have never seen in the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s many films, but still maintains his cool mystery. “Loki’s a mercurial shapeshifter who seems to present one thing on the external when there’s perhaps another thing going on in the internal,” Hiddleston says. “He’s always worn many masks.”

And in this series, he’s getting a whole new look: a prison uniform. The story kick-starts where we last saw the prankster, 2019’s Avengers: Endgame film. In an alternate post–Battle of New York 2012 timeline, Loki absconded with the Tesseract cube containing the megapowerful Space Stone, which grants him the ability to portal throughout space. Smart planning, Marvel! “We knew we were going to take Tom off on his solo story,” executive producer Kevin Feige admits.

This Loki is a darker, meaner god; he hasn’t yet undergone all that brotherly character development from Thor: The Dark World, Thor: Ragnarok, and Avengers: Infinity War. The bright side? You won’t have had to see all the latest films to understand what’s going on.

When we catch up with Loki, his stealing the Tesseract has led to his imprisonment by the bureaucratic Time Variance Authority, formed to “ensure that time unfolds according to its predetermined outcomes,” explains Hiddleston. They are basically the timeline police, and he’s in big trouble.

Loki’s been stripped of his powers and his trademark green and gold ensemble, making him more human than ever. But don’t expect that to dim his light. “You can take his scepter away, you can take off the cape and the fine Asgardian leather and literally put him in a button-down shirt and pants, and he’s still Loki — he’s more Loki than you’ve ever seen,” Feige says, playfully adding: “And that’s not just because Tom Hiddleston looks good in any clothes at all, but he does.”

Luckily for Loki, the TVA needs his help to track down a killer who’s wreaking havoc on the timeline. Reluctant yet powerless, the inmate has no choice but to say yes. (In the trailer, Loki appears to drop in on Pompeii’s collapse and seemingly becomes ’70s plane hijacker D.B. Cooper, so his time jumps, whether sanctioned by the TVA or not, are pretty bold too.)

TVA agent Mobius M. Mobius (Owen Wilson, sporting a bushy moustache) is assigned to keep Loki on a very short leash. Mobius’ delighted fascination — he holds “the highest academic honors in the studies of Loki,” notes Hiddleston — makes the manipulator even more guarded than usual. “It’s a little bit of a chess match to gain Loki’s trust, but in that shared endeavor, there’s an interesting dynamic,” says Wilson, who likens the partnership to “Nick Nolte getting Eddie Murphy out of jail in [the 1982 movie] 48 Hrs.” For his part, Feige predicts Loki and Mobius “will be one of the most popular pairings we’ve ever had at Marvel.”

Viewers can also anticipate some ambiguity, as in Marvel’s latest TV forays, WandaVision and The Falcon and the Winter Soldier. Both had watercooler moments (“It was Agatha all along!”) but also plenty of plot and character details left as question marks (we don’t know who Sophia Di Martino is playing either). And while Hiddleston says the key element that makes Loki a fan favorite is his ability to astonish viewers, this adventure could leave a certain god the surprised one. “What we try to ask is, behind the slippery trickster, who is he really?” the actor says. “Does he even know?” You can bet the discovery will be a lively, ruse-filled ride.

230 notes

·

View notes

Text

For a roughly 3,000-year-old god, Loki sure isn’t showing his age. In the trippy six-episode Disney+ series that bears his name, he’s full of his usual maniacal vigor and charm, and no wonder: This time, Tom Hiddleston’s god of mischief — first introduced in 2011’s big-screen Thor as the troublemaker, shapeshifting brother of Chris Hemsworth’s god of thunder — takes center stage.

Loki, a time-traveling procedural drama, opens up the complex character in ways fans have never seen in the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s many films, but still maintains his cool mystery. “Loki’s a mercurial shapeshifter who seems to present one thing on the external when there’s perhaps another thing going on in the internal,” Hiddleston says. “He’s always worn many masks.”

📷SEE ALSO'Loki' Sneak Peek: Owen Wilson and Tom Hiddleston Meet For First Time (VIDEO)Marvel Studios introduces Agent Mobius in clip from six-episode series.

And in this series, he’s getting a whole new look: a prison uniform. The story kick-starts where we last saw the prankster, 2019’s Avengers: Endgame film. In an alternate post–Battle of New York 2012 timeline, Loki absconded with the Tesseract cube containing the megapowerful Space Stone, which grants him the ability to portal throughout space. Smart planning, Marvel! “We knew we were going to take Tom off on his solo story,” executive producer Kevin Feige admits.

This Loki is a darker, meaner god; he hasn’t yet undergone all that brotherly character development from Thor: The Dark World, Thor: Ragnarok, and Avengers: Infinity War. The bright side? You won’t have had to see all the latest films to understand what’s going on.

When we catch up with Loki, his stealing the Tesseract has led to his imprisonment by the bureaucratic Time Variance Authority, formed to “ensure that time unfolds according to its predetermined outcomes,” explains Hiddleston. They are basically the timeline police, and he’s in big trouble.

Loki’s been stripped of his powers and his trademark green and gold ensemble, making him more human than ever. But don’t expect that to dim his light. “You can take his scepter away, you can take off the cape and the fine Asgardian leather and literally put him in a button-down shirt and pants, and he’s still Loki — he’s more Loki than you’ve ever seen,” Feige says, playfully adding: “And that’s not just because Tom Hiddleston looks good in any clothes at all, but he does.”

Luckily for Loki, the TVA needs his help to track down a killer who’s wreaking havoc on the timeline. Reluctant yet powerless, the inmate has no choice but to say yes. (In the trailer, Loki appears to drop in on Pompeii’s collapse and seemingly becomes ’70s plane hijacker D.B. Cooper, so his time jumps, whether sanctioned by the TVA or not, are pretty bold too.)

TVA agent Mobius M. Mobius (Owen Wilson, sporting a bushy moustache) is assigned to keep Loki on a very short leash. Mobius’ delighted fascination — he holds “the highest academic honors in the studies of Loki,” notes Hiddleston — makes the manipulator even more guarded than usual. “It’s a little bit of a chess match to gain Loki’s trust, but in that shared endeavor, there’s an interesting dynamic,” says Wilson, who likens the partnership to “Nick Nolte getting Eddie Murphy out of jail in [the 1982 movie] 48 Hrs.” For his part, Feige predicts Loki and Mobius “will be one of the most popular pairings we’ve ever had at Marvel.”

Viewers can also anticipate some ambiguity, as in Marvel’s latest TV forays, WandaVision and The Falcon and the Winter Soldier. Both had watercooler moments (“It was Agatha all along!”) but also plenty of plot and character details left as question marks (we don’t know who Sophia Di Martino is playing either). And while Hiddleston says the key element that makes Loki a fan favorite is his ability to astonish viewers, this adventure could leave a certain god the surprised one. “What we try to ask is, behind the slippery trickster, who is he really?” the actor says. “Does he even know?” You can bet the discovery will be a lively, ruse-filled ride.

Loki, Series Premiere, Wednesday, June 9, Disney+

This is an excerpt of TV Guide Magazine’s latest cover story. For more of the exciting, action-packed fun, pick up the Sci-Fi Spectacular issue, on newsstands Thursday, June 3.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cape Crozier: The Outward Journey

As always, please visit the original blog for proper formatting. Sigh, Tumblr.

I am telling this as the last of my field trips, because it was without doubt the climax of my Antarctic adventures. In actual fact, this happened the day after the previous climax, which was when I flew over the Beardmore Glacier. If time was invented so everything didn't happen at once, and space was invented so it didn't happen to you, then Time and Space were apparently out on a girls' weekend in late November 2019.

There was one major journey yet to undertake, in my visits to sites of historical importance. It was the location of a minor side-quest in the story of the Scott Expedition – one could, theoretically, leave it out of a retelling with no narrative consequences – but it's the central episode and emotional fulcrum of The Worst Journey in the World, and gave the book its title. In June and July 1911, the dead of Antarctic winter, three men set off from Cape Evans to reach the Emperor penguin colony at Cape Crozier, on the other side of Ross Island, to fetch some eggs when the embryos were at the right stage of development to yield potential clues to the evolution of birds. The adventure ended up being more of a test of human endurance than avian ancestry, and the results got from the few specimens they did collect did not advance the theory they were hoped to prove (though scientists would remind us that negative results are still results). However, it is an amazing story of what people are willing to undertake for the sake of intellectual progress, and in this instance, of how cast-iron character can make the unimaginably awful endurable, and as such, it very much warrants the retelling.

Unlike Cape Evans, Cape Crozier is hard to get to, hostile, and not very well documented. There was no way I could ever visit it at midwinter, but, having almost no clue what the place was like beyond the written word, it was vitally important to me to stand there myself and get a sense of the geography, so that I could draw figures groping around it in moonlight and blizzard when the time came. Luckily the NSF agreed that it was important I go, because it was the most complex and expensive trip to arrange. It would necessitate a helicopter ride; helicopters cost so much to fly, and are so necessary for shuttling people and stuff around any part of Antarctica that is inaccessible by plane (which is most of Antarctica), that their use is very strictly rationed. I had exactly enough helicopter time allocated to get me to Cape Crozier and back. Therefore, we had to fly on a day when it was absolutely certain we would not have to turn around, because an aborted trip would mean I didn't have enough flight hours left to try again. Antarctic weather is unpredictable and Cape Crozier has a reputation for turning very nasty very fast, so this needed to be a careful judgement call.

The first day it was posited I fly, it didn't happen – I forget why; I think there was a backup in other jobs, and mine, being of low importance, got dropped to make room. The second time, I was slotted for 3:45pm, though with one eye on the weather and the other on resources, the right was reserved to cancel at any time. A little after 2:30 my coordinator called to say we were, as far as anyone could tell, good to go, so to meet at Helo Ops at 3 for the safety briefing and helmet fitting.

Accompanying me to the far reaches of Ross Island would be my coordinator, who had been a few times before; the pilot, who was one of the best in the biz and had flown for pretty much any Antarctic documentary you care to name; and a biologist, who was required to go because Cape Crozier hosted a rare and fragile species of Antarctic lichen, which we must be careful not to step on or disturb in any way. The biologist who usually went on these trips was feeling unwell, so she sent a replacement, who was very happy to have the opportunity as he had never been to Cape Crozier before. Of course, this meant he didn't know what the lichen looked like, but we would doubtless find out when we got there.

Team assembled and briefing done, we had only to wait for the flight to be activated. The last possible moment came and went without cancellation, so we were on.

The latest weather report from the station at Cape Crozier was that it was 30% cloudy with winds at 7 knots. Keeping an eye on the wind was important for obvious safety reasons; the cloud conditions, though, were important for less obvious reasons. The helicopter pilot needs shadows and detail to be able to tell how far away the ground is, either to stay in the air or to make an emergency landing. When clouds diffuse sunlight, a snow-covered surface looks perfectly blank, and no details show up to give a sense of scale or distance, so it's unsafe to fly.

We were supposed to have flown along the south coast of Ross Island, following the route that Wilson, Bowers, and Cherry-Garrard sledged at great cost in 1911. That side of the island was cloudy, however, so we were redirected to fly around the other side. From a historical perspective this was a bit of a disappointment, but from an artistic one, the north side of the island was absolutely stunning, and I very quickly came to see why people with money to burn choose to travel by helicopter.

Plus, it meant we started out journey by flying over Cape Evans.

All of Ross Island is volcanic, and near Cape Royds is a small parasitic cone which was explored by the expedition's geologists, who were also the first to climb Mt. Erebus. I thought it was named Mt. Sis, after someone's sister, but in fact it is Mt. Cis, after one of their dogs. Our pilot had been this way before and had something special to show us:

On top of Mt. Cis is a pickaxe. I don't believe there's any historical record of anyone leaving it there, but the Nimrod Expedition is not my speciality. It has been checked out, and the pickaxe is a model that was in use in the early 20th century, so either an early explorer stuck it there and didn't bother writing it down, or a later explorer found an old pickaxe and stuck it there to give the impression an early explorer had done so. Anyway, it's been there as long as anyone can remember, and doesn't seem to have suffered much, so will probably continue to be there for some time to come.

From there, onwards up the east coast to cross over the shoulder between Mt Erebus and Cape Bird, then over the snowy slopes of Terror, and the dissipating sea ice, to reach our destination.

Our first sight of Cape Crozier was the Adélie penguin rookery. This is one of the largest in the world, where upwards of 250,000 penguins congregate to make the next generation of penguins every year. I had not seen a penguin yet, and though my eyeballs were pointed directly at them, I was too far up to see any now, but their presence is evident in the vast, vast amount of light brown penguin poo.

On this side of Ross Island, the ice shelf is unimpeded by smaller islands or awkward quirks of geology as it is around McMurdo. As it grinds around the corner, here, it crinkles, and then as it straightens out again, the crinkles break, and the ice lets in long fingers of sea, which freezes during the winter. It is on these frozen fingers, sheltered from the worst of the blizzards by the taller segments of Ice Shelf, that the Emperor penguins incubate their eggs through the Antarctic winter.

It was these finger bays that our intrepid explorers were trying to reach, but they needed to establish their base camp somewhere a little more secure, on the solid rock of Cape Crozier. We were on our way to do the same.

The hill coming up was incredibly exciting to see, perhaps even more exciting than Observation Hill. When the Terra Nova first arrived at Ross Island, it was not on the McMurdo side of it, but rather here, because Cape Crozier was posited to be the most sensible site for Expedition headquarters. It had been explored on the Discovery Expedition, so they knew there was permanent access to the ice shelf, and thus the road south, unlike Hut Point or Cape Royds which would be cut off by miles of open sea for half the year. It had reliable fresh water nearby, and the Emperor penguins would be right next door. On the day the Terra Nova arrived, though, the swell on the sea was too high to permit a landing, and when they sent out a scouting party on one of the whaleboats, they discovered no suitable landing place. So they had no choice but to make for the old familiar haunts on the other side of the island.

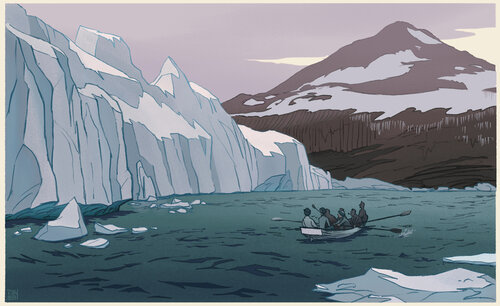

Now, this is so much historical trivia, except that as part of exploring my desired artistic style and putting together my grant proposal for this trip, I had drawn that scouting journey, and prominent in the scene is this very hill, with its orca eye-spot of snow. The early explorers called it The Knoll.

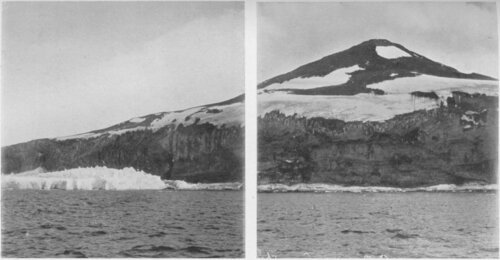

This was based on a photograph taken on that day, which clearly shows The Knoll, and also that in January 1911 the ice front was a very long way back from where it is now.

As you can see, what is open water in 1911 is thick and pressured ice in my own photo from 2019.

Now, before you jump on this as proof that climate change is a lie, you may like to hear about my conversation with a scientist who has been studying the Cape Crozier Emperors for over forty years. He said that, while usually the leading edge of the ice shelf crumbles into small icebergs, occasionally enormous chunks drift off in one go. When they do, they take a whole generation of Emperor chicks with them, long before they are ready to swim, and that generation is lost. There is another Emperor colony at Beaufort Island, off the north coast of Ross Island, and following a catastrophe at Cape Crozier, a lot of breeding pairs move to Beaufort, and vice versa.

When the Crozier party arrived at the Emperor rookery in July 1911, Wilson was expecting the two thousand birds he'd seen when he visited with the Discovery, but there were only a hundred. Therefore it is plausible that, sometime between 1903 and 1911, a very large chunk of ice had pulled away from Cape Crozier, pushing the shoreline back and scaring off the penguins.

Back to the present, now, or at least last November. We had just passed The Knoll and were on our way to our landing site, a short walk away from the site of our penguin hunters' stone igloo. The place they chose to call home is the thin little ridge sticking out into the mist at the left of this photo:

Here we come …

And there we are.

When the Crozier party set off on their science trip in 1911, the three men hauled two sledges for two and a half weeks, through deep soft snow and temperatures that broke known records – down to -77°F one night, according to the thermometer slung under the sledge. The transcendent misery of marching in frozen clothes, not being able to get proper sleep for the shivering, and burning their precious fuel through the night just to survive, is carved deep in Cherry's writing of the experience. To say it was hellish is no exaggeration: Cherry points out that Dante put the circle of ice below the circles of fire in his Inferno, and thought it was apropos. The greatest challenge of our own journey out was landing the helicopter: given the sensitive environment and the fragile lichens, there was a specific landing site that was supposed to be marked out with stones. Our pilot circled once to find it, and came back around because he couldn't spot it the first time, then finally landed right on the GPS waymark because there was no visible clue where the actual site was supposed to be. As difficulties go, it hardly bears mention. Whether we'd earned it or not, however, we were there.

#antarctica#cape crozier#helicopter#travel#photography#photos#winter journey#the worst journey in the world#apsley cherry-garrard#edward wilson#birdie bowers#henry robertson bowers#edward adrian wilson#bill wilson#emperor penguins#science#adventure

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Adventures of David Dashiki-Story of an African American Hero- Damn...Not Again ! ! !

Please Not Again...Another unarmed Black man killed by the police. This is the pandemic that has never been addressed. This is the criminality and brutality that make Black mothers weep and moan. This is the savagery that America has ignored for too long.

Imagine all of the time we have had to fight for our lives because white people have attempted to kill us. We have answered in peace marches, voting, boycotting, law suits and still we die.I have heard the voices of whites complaining that the police are not the problem. They are for us. Four hundred years and still no peace. Again after the Chauvin verdict, we have to bring the problem of murder by the police as a serious matter in the lives of Black citizens. We have to be ready for it everyday. Daunte Wright was murdered in Minnesota. Andrew Brown was assassinated in North Carolina. Police in that state refused to release the video of the killing. ...even to the family. Finally, family members were granted the opportunity to view the police activity in the case, but only a twenty second redacted version. This is further insult. In the killing of your son , brother, father, relative , you are still without rights. Who makes these laws.? Why?

Andrew Brown was fleeing the police. He was shot four times in the arm. Then the golpe de gracia was a bullet to the back of the head. Believe me I want to write about happy days. We are in the final days of conquering a disease that has killed over 500,000 citizens. We have overcome the effects of 4 of the most disastrous years in American History. We voted in enormous numbers and elected a man with character and vision. We are attending classes again, dining out and going to sporting events. Families are reuniting in the parks and playgrounds.Couples are strolling the streets, holding hands and smiling. Yet, we cannot eradicate this national shame which controls us...Racism !. These were human being killed in America for the color of their skin.These were no accidents. Roof who killed 9 members of a church while in bible study, is serving time. The rogues who stormed the Capitol only lost one member of their group to a gunshot which killed her. So, there are ways to serve as a policeman without murdering unarmed Black men. We are Americans too We have to tell America the truth. We have to continue to speak out any time our rights are violated. We must. Some might not like to hear it. For us, it is a matter of life and death

There was a film by Ava Duvernay which intelligently and beautifully demonstrates the phenomenon of the inclination for policemen to shoot to kill unarmed Black men in any interaction and encounter. ‘When They See Us’ . would be an excellent training video for all policemen and especially white officers assigned to work in African American Neighborhoods. These cops just see us differently. They envision us as criminals and only that. They do not visualize us as even human beings. And as there is no training in human relations between the officer and the community, the policemen come to work with their attitude of hunter in the wild. In contrast, when I leave my home, I depart with joy and happiness. Today I’m going to encounter my lovely brothers and sisters. I will have the wonderful opportunity to engage the descendants of kings and queens,. I have the occasion to learn from the bravest, most creative and loving people on earth. These charismatic people have never changed their attitude toward one another in spite of so many years of persecution and torture in this land. Dr. Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, Barack Obama, Muhammad Ali, Oprah Winfrey, W.E.B. DuBois, Frederick Douglass, Alvin Ailey, Richard Allen, Ella Baker, Benjamin O Davis, Mary McLeod Bethune, Dr. Charles Drew, Dr. Keith Black, Percy Julian, Thurgood Marshall, Toni Morrison, Jackie Robinson, Ida B. Wells, August Wilson, Madam C.J. Walker, Gordon Parks, Bessie Coleman, Serena Williams, Dr. Mae Jemison, Dr. Ernest Everett Just, Dr. Neil DeGrasse, Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson, Dr. Ayanna Howard.. The police would act differently and respect us if they knew our history. How many other scientists, lawyers, doctors and authors have we lost in these murders? No other race is besieged by such persecution and slaughter, then cover up and lack of transparency as we...We are target practice for the police. I was on the internet recently and spotted an article which dealt with the theme of a designated period for the hunting of the certain species so that the herd might be replenished...’DAMN, EVEN WILD ANIMALS HAVE AN OFF SEASON !!! Perhaps America is not that civilized yet as to impose the law that the season for the execution of unarmed Black men has ended

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Utopia US Remake Ending Explained: Who is Mr Rabbit?

https://ift.tt/3kvTqix

Warning: contains major Utopia spoilers

With newly invented characters and a whole new world wrapped around bad guys/pragmatic planet savers The Harvest (the US version of The Network), Gillian Flynn’s Utopia makes considerable changes to the Channel 4 original. It’s faithful though, in most of the ways that matter – Jessica Hyde, the unforgettable Arby, Wilson Wilson and more are all kept intact, just transplanted from London to Chicago. There’s some very close translation of a few memorable scenes, as well as a good amount of invention. Flynn rewrites the backstory to weave in new setting ‘Home’, and new players, chief of which are John Cusack‘s Dr. Kevin Christie and Rainn Wilson’s Dr. Michael Stearns (the latter a sort-of combination of the original’s Michael Dugdale and scientist Donaldson).

Flynn’s series takes the bold step of taking us inside the shady global organisation pulling the strings of global virus outbreaks, and building an unsettling cult mythology around it with its own tagline: what have you done today to earn your place in this crowded world? Well, in our case, we’ve sorted through the many threads of the Utopia remake finale to explain anything viewers may have missed the first time around… Major spoilers ahead.

Who is Mr Rabbit?

‘Christie and I have parted ways, he just doesn’t know it yet.’

It seems that both Christie and Milner are ‘Mr Rabbit’, i.e. the head of shadowy bio-warfare/new society group The Harvest. Both have the Chinese symbol for rabbit carved into their torsos, and both worked together on the production of viruses for use as germ-warfare post 9-11. The mysterious Milner (The Wire‘s Sonja Sohn), however, told Jessica that she and Christie had parted ways, though he didn’t know it yet, pointing the way to a potential rivalry should there be a second season.

What is The Harvest?

It’s the organisation started by Christie and Milner, which is behind the introduction of man-made viruses into the population. Its ultimate purpose, or at least, Christie’s purpose, is to sterilise the global population for three generations, thereby forcibly reducing overpopulation and the strain it places on the planet’s natural resources.

What is Home?

‘A new society, a grand social experiment’

The headquarters of The Harvest, where children (especially twins – matching pairs are useful in genetic studies) are shipped in from impoverished countries all over the world and brainwashed in Christie’s beliefs. Some are experimented on, some are trained –like Arby – to be assassins, others are trained to sacrifice themselves as martyrs. They’re all taught to respect the ‘purpose’ assigned to them, and to end each day by asking what they’ve done to earn their place in this crowded world.

What is hidden inside the Flu vaccine?

‘You won’t be having any children’

A sterilisation gene that’s passed down for three generations, stopping anybody who got the vaccine from having children during that time. It’s part of Christie’s Thanos-alike plan to reverse global overpopulation and reduce the pressure it puts on scarce natural resources, which he predicts would lead to the “war of wars”.

What happened to Jessica in that yellow house?

‘Your father created you for me’

She was gassed and experimented on as a child, her body used to test viruses, vaccines and genetic behavioural modifications. The ‘presents’ she remembers being delivered were crates of children purchased from their parents in poverty all over the world, there to be used as lab rats, or trained as soldiers or martyrs. When ‘Mr Rabbit’ used to give Jessica cookies, presumably they were infected with various flus against which she’d been vaccinated. (Or maybe they were just cookies? He does love kids, after all.) Jessica lived there alone, being experimented on by her father, until Artemis (a combination of UK character The Tramp and Jessica’s unseen trainer/saviour Christos, whom a 15-year-old Arby tortured to death) broke them both out, hiding Jessica’s father in an institution and taking the girl on the run.

Who was the man in Jessica Hyde’s basement?

‘My dear, he didn’t care about you at all’

Jessica’s father, the scientist who drew the Dystopia and Utopia comics, and who manufactured multiple viruses during his time working for The Harvest. When Artemis sprang young Jessica and her father from Home and took them on the run, she hid Jessica’s father in an insane asylum (the same one Dr Mike was checked into by his Harvest sleeper agent/wife Maureen), before Milner presumably had it burned to the ground, taking Jessica’s father and imprisoning him in the basement underneath the yellow house.

Read more

TV

Utopia Review (Spoiler-Free)

By Lyra Hale

TV

Utopia: How the US Remake Changes the UK Show’s Most Controversial Sequence

By Louisa Mellor

Is Milner Jessica’s biological mother?

‘I’m not Homeland, I’m Home’

There’s nothing to suggest that Jessica wasn’t simply part of a shipment of children, raised by her scientist ‘father��� in the same way that Dale was given twins Charlotte and Lily to raise as his own. However, there’s a chance that she could be her father’s biological child, and if so, there’s also a chance that Milner is her biological mother (though at this stage, we’re only in the realm of mad speculation.) Arby does call Jessica his sister, but presumably he’s talking figuratively in light of their shared childhoods as lab rats.

Why did Arby/John betray The Harvest?

‘Every child needs love, I think’

Because he read the Utopia pages he’d taken from Grant, and realised that The Harvest had subjected him to experiments as a child that turned him into an unfeeling monster able to commit brutal acts without feeling remorse. Arby (a modification of the initials R.B, which stood for Raisin Boy, the name the Harvest scientists gave him because of his fondness for chocolate-covered raisins – he didn’t even have a name) realised that Harvest had mistreated him, and so decided to choose his own name – John – and his own purpose: to help his ‘sister’ in experimentation, Jessica Hyde.

Why was Wilson Wilson with Thomas and Christie in the end?

‘Everything I do is a cure for our current situation.’

Because (unless he’s playing the double agent game) Wilson Wilson had come around to Christie’s way of thinking, and so betrayed the group. As its most fringe member, and a believer in conspiracy theories, Wilson felt that Christie was right about global overpopulation (remember his frustration about Dr Mike and the rich oligarch whose house they crashed at having too many belongings?). Wilson, we can assume, has now joined The Harvest as one of Christie’s followers, despite The Harvest having murdered his family.

Why didn’t Dr Mike destroy the vaccine’s mother egg?

‘Whoever holds the egg holds the power’

When Dr Mike destroyed the eggs in which the vaccines were stored, it was assumed he also destroyed the mother-egg containing the source of the sterilisation vaccine that Christie Labs were preparing to send out all over the United States. The last we saw Dr Mike, he was driving out of Chicago with the mother-egg intact. After being used and manipulated by Christie and The Harvest, he’s taken the vaccine mother-egg to use as a bargaining chip.

How did Jessica get the T-shaped rash flu and why didn’t she die?

‘Your blood is slowly saving you.’

On the drive back from destroying the bunnies at the travelling petting zoo that was spreading the ‘Stearns’ flu around US schoolchildren, Jessica was bitten on the finger by the white rabbit the gang had taken for Dr Mike to test. She was thus infected with the flu and started to develop its characteristic T-shaped forehead rash. Dr Mike discovered that the rabbit was infected with flu, but it was a different strain to the one he’d developed a vaccine for. That told him that the vaccine in production at Christie Labs wouldn’t cure the T-shaped flu – that was all just pantomime to get Americans clamouring for the vaccine – so it must have been designed for another secret purpose (see above).

What were all those marks on Jessica’s back?

‘Thanks to you, humans will be immune from acting with greed.’

The constellation of different shaped marks on Jessica’s back, like her ‘starburst’ arm mark, are scars from various vaccinations and experiments her father and Milner performed on her. Milner and Jessica’s father were working on genetic modifications to human behaviour, forcing people to “act correctly” by taking away their free will. Inside Jessica Hyde’s blood is a whole bunch of vitally important genetic information, which is why Milner needed Jessica herself back at Home. The Harvest’s search for the Utopia manuscript was only ever intended to bring Jessica back after Artemis smuggled her and her father out when she was a child.

How did Becky contract Deel’s Syndrome?

‘What we are doing is far bigger than death.’

She was deliberately infected with it by The Harvest when they sent the disease out into US schools in order to test whether they could introduce a virus into humans that would then be passed on genetically, as a dress rehearsal of the sterilisation plan.

Where did everybody end up?

‘We won, we wiped you out.’

Jessica is currently being held captive by Milner, along with her father, at Home. Becky was captured by Thomas, Christie and Wilson Wilson, who appears to have gone over to the dark side. Grant (still wanted for the killing of Cara’s family) was captured by the police. Alice and Ian were left on the run together. And Dr Mike was last seen driving out of Chicago with the ‘Stearns Flu’ vaccine mother-egg in his possession.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

Utopia is available to stream now on Amazon Prime.

The post Utopia US Remake Ending Explained: Who is Mr Rabbit? appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3681MZI

0 notes

Text

2017 Reading Challenge 25/52 A Book That’s Been Mentioned In Another Book Paradise Lost - John Milton (Frankenstein)

Ironically, I haven’t read the book that it was mentioned in yet (this year, I’ve read it before).

Boy was this one a slog. Even as an audiobook, I just kept zoning out while I listened. I studied it at uni, and never read it, but it sounded like a really cool story. And I’ve always liked poetry, but this was something else. Not for me.

I’ve started The Bell Jar, but haven’t looked at it in weeks. It’s fairly short though, so I should push through it in one day, whenever that day comes. I might buy up a few audiobooks to listen to at work this week. Gotta at least hit 26 books, but hoping for 30.

A book recommended by a librarian The Secret Garden - Frances Hodgson Burnett

A book that’s been on your TBR list for way too long IT - Stephen King

A book of letters Frankenstein - Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

An audiobook Wishful Drinking - Carrie Fisher

A book by a person of colour The Prey of Gods by Nicky Drayden

A book with one of the four seasons in the title A Midsummer Night’s Dream - William Shakespeare

A book that is a story within a story The Name Of The Wind - Patrick Rothfuss

A book with multiple authors Good Omens - Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman

An espionage thriller Casino Royale - Ian Fleming

A book with a cat on the cover Doctor Sleep - Stephen King

A book by an author that uses a pseudonym Feedback - Mira Grant (Seanan McGuire)

A bestseller from a genre you don’t normally read Murder On The Orient Express - Agatha Christie

A book by or about a person who has a disability Labyrinths - Jorge Luis Borges

A book involving travel The Great Railway Bazaar - Paul Theroux

A book with a subtitle Twelfth Night (or What You Will) - William Shakespeare

A book that’s published in 2017 Norse Mythology - Neil Gaiman

A book involving a mythical creature Wrath of a Mad God - Raymond E Feist

A book you’ve read before that never fails to make you smile Guards Guards - Terry Pratchett

A book about food My Berlin Kitchen: A Love Story (with Recipes) - Luisa Weiss

A book with career advice On Writing - Stephen King

A book from a nonhuman perspective Charlotte’s Web - EB White

A steampunk novel Perdido Street Station - China Miéville

A book with a red spine Flight Of The Nighthawks - Raymond E Feist

A book set in the wilderness A Walk In The Woods - Bill Bryson

A book you loved as a child Wild Magic - Tamora Pierce

A book by an author from a country you’ve never visited 1Q84 Part 1 - Haruki Murakami

A book with a title that’s a character’s name Hamlet - William Shakespeare

A novel set during wartime All Quiet on The Western Front - Erich Maria Remarque

A book with an unreliable narrator Gone Girl - Gillian Flynn

A book with pictures The Type - Sarah Kay

A book where the main character is a different ethnicity than you Invisible Man - Ralph Ellison

A book about an interesting woman Mullumbimby - Melissa Lucashenko

A book set in two different time periods Kindred - Octavia E Butler

A book with a month or day of the week in the title A Local Habitation (October Daye) - Seanan McGuire

A book set in a hotel The Shining - Stephen King

A book written by someone you admire Alif The Unseen - G Willow Wilson

A book that’s becoming a movie in 2017 Hidden Figures - Margot Lee Shetterly

A book set around a holiday other than Christmas The Thanksgiving Visitor - Truman Capote

The first book in a series you haven’t read before Rosemary and Rue (October Daye) - Seanan McGuire

A book you bought on a trip Purple Hibiscus - Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Advanced

A book recommended by an author you love Difficult Women - Roxane Gay

A bestseller from 2016 The Girl On The Train - Paula Hawkins

A book with a family-member term in the title Dreams From My Father - Barack Obama

A book that takes place over a character’s lifespan The Curious Case of Benjamin Button - F Scott Fitzgerald

A book about an immigrant or refugee The Refugees - Viet Thanh Nguyen

A book from a genre/subgenre that you’ve never heard of The Grace of Kings - Ken Liu (Silkpunk)

A book with an eccentric character Into A Dark Realm - Raymond E Feist

A book that’s more than 800 pages The Wise Man’s Fear - Patrick Rothfuss

A book you got from a used book sale X-Factor Volume 1 #70-71 - Peter David et al

A book that’s been mentioned in another book Paradise Lost - John Milton (Frankenstein)

A book about a difficult topic The Bell Jar - Sylvia Plath

A book based on mythology Throne of the Crescent Moon - Saladin Ahmed

1 note

·

View note

Text

Musings on A Study in Pink (1)

Trigger Warning (General): Mentions and discussion of homophobia and suicide

More specific trigger warnings will precede each part of the meta

Summary: The theme of the show has been clear since day one. Heteronormativity, homophobia, and toxic masculinity will kill John, Sherlock, and Johnlock if the former are not stopped.

This meta is a series with three parts:

Part 1: Shot in the left shoulder – the Cabbie as a John mirror

Part 2: ‘You can’t have serial suicides’ – media, chain suicides, and social problems

Part 3: ‘Who’d be a fan of Sherlock Holmes?’ – The biggest obstacle to Johnlock

All transcripts taken from Ariane Devere Sherlock episode transcripts. Appropriate pages will be linked after each quote.

All S1-S3 screenshots taken from screencapped.net

Part 1: Shot in the left shoulder – the Cabbie as a John mirror

TRIGGER WARNING: Discussions of homophobia and suicide; image of fake but realistic blood

The main flow of the case in ASiP goes like this: the Cabbie is one of those ‘just want the best for his kids’ parents. He is diagnosed with a terminal illness. Motivated and enabled by Moriarty, he goes on a potentially fatal murder spree, leaving four people dead in his wake. Sherlock eventually solves the case, but the Cabbie is ultimately stopped by John.

In short, the main characters at play are: Moriarty, Cabbie, Sherlock, and John. Moriarty and the Cabbie are the main enigmas. What do they represent?

In Part 1 we will focus on the Cabbie and what he might stand for.

The Cabbie: the ‘this is for your own good’ homophobic parent

One important thing to note is that while the deaths appear to be suicides, they technically aren’t – they are murders. The Cabbie forced the victims to take their own lives. So what exactly motivated the Cabbie to go on this killing spree?

SHERLOCK (thoughtfully): No. No, there’s something else. You didn’t just kill four people because you’re bitter. Bitterness is a paralytic. Love is a much more vicious motivator. Somehow this is about your children.

…

JEFF: When I die, they won’t get much, my kids. Not a lot of money in driving cabs.

…

JEFF: For every life I take, money goes to my kids. The more I kill, the better off they’ll be. You see? It’s nicer than you think. [x]

Sherlock correctly points out that the Cabbie is motivated by what the latter believes to be love for his children—a love that manifests in a rather twisted and bloody way, in this case. He believes he has his children’s best interest in his heart, but he leaves behind a bloody trail. Even if his children do end up getting the money, they are bloody money. If the Cabbie takes the wrong pill and dies, there is no promise the money will arrive at the hands of his children. He believes what he is doing is good for the kids, but in the end, the kids very likely will not benefit from it.

Remind you of anything? To me it sounds like the kind of homophobic parents who want their kids to ‘stop being gay’ because they ‘love’ them. ‘I don’t want you to be bullied or hated by the society so stop being gay’ kind of parent.

What the Cabbie does for a living seems to support this reading, too. The Cabbie drives a cab around (duh). But wait—what exactly are the words used to describe him in the show?

The Cabbie, or the London cabs, ‘passes unnoticed wherever they go’, and the Cabbie ‘hunts in the middle of a crowd’ [x]. Or, in the even more poetic words of Pilot!Sherlock, the cabs are cars that ‘pass like ghosts, unseen, unremembered’; we would willingly and perhaps unconsciously trust them: ‘every day we disappear into their cars and let the trap close around us’.

In short, as Pilot!Sherlock says, the London cab, these public cars, is ‘the invisible car’, ‘the perfect murder weapon of the modern age’. [x]

What do cars mean? @the-7-percent-solution explained, in this short meta, that ‘a way of implying male virility in writing is through the use of cars’. In this sense, then, the London cab represents a kind of male virility that can ‘hunt in the middle of a crowd’, implicitly trusted and taken for granted. In the sexual understanding, the type of male virility that could hunt in the crowd without attracting attention would be straight male virility.

In other words, the Cabbie is basically cruisin’ around London with his car of murderous heteronormativity, hunting down closeted people.

ASiP Recap: the Cabbie’s victims as John mirrors

It is established in the fandom that all victims of the Cabbie are John mirrors [x]. Let’s take a quick look again at who exactly are killed by the Cabbie:

A knight of the realm, locked in a loveless marriage while having an affair with a cutie wearing a purple silk shirt

A young man who fears he would look gay if he shares an umbrella with his friend

(This is a line deleted from ASiP, in the scene where the young man says he’s running home to grab an umbrella because he does not want to share his friend’s.)

SHERLOCK: Take my hand.

JOHN (grabbing his hand as they race onwards): Now people will definitely talk. [x]

An MP who has a drinking problem and tends to drink-drive unless intervened

Jennifer Wilson: another who is locked in a loveless marriage, having a string of lovers, and has a stillborn daughter whose initial was RW.

Specifically, all the Cabbie’s victims are mirrors of John after he meets Sherlock. (John might have had a drinking problem before he meets Sherlock, but it seems particularly serious after TRF; there are a lot more references to him drinking.)

As mentioned above, the Cabbie subtextually stands for heteronormativity and homophobia. In other words, John, in all these incarnations, is killed by heteronormativity and homophobia. But wait, there’s more to the Cabbie.

Cabbie as a John mirror

TJLCE lays out the following as signs that a minor character is a mirror [x]:

They look like a main character

They dress like a main character

They have the same name as a main character

They act like/speak like/are in a situation similar to the main character

They hang out in front of mirrors

There are several signs that the Cabbie may be a mirror for John. They both wear knitted jumpers/cardigans. They both have light-coloured hair. John and the Cabbie look just similar enough that one would try to connect the two. Besides, both John and the Cabbie are shot in the left shoulder.

(Some say he is shot in the heart, but it is unclear on screen, and the locations of the shots seem close enough that we can assume they are shot in a similar spot.)

SHERLOCK: In Afghanistan. There was an actual wound.

JOHN: Oh, yeah. Shoulder.

…

SHERLOCK: The left one.

JOHN: Lucky guess. [x]

The Cabbie is also the first person on the show, apart from John, to be shown in possession of a (fake) gun. More importantly, he embodies both life and death like John.

Cabbie: good pill (life), bad pill (death)

John: being a doctor (life), being a soldier (death)

These are all clues that the Cabbie is some kind of John mirror; specifically, the Cabbie is a mirror of John in the army: John is an army doctor and is shot in the left shoulder during his time in the military, and owns a gun because of his military background.

In short, the Cabbie is an army!John mirror.

But there’s more.

Cabbie as a mirror of John’s dad

While writing on the Cabbie as a John mirror, I could not seem to get very far with that analysis. That is when I started noticing details that seem to suggest the Cabbie can be read as an image of John’s dad.

I mentioned above that the Cabbie looks similar enough to John that we can make the connection. While similar, he looks quite a lot older than John’s age, which is early to mid-thirties. In fact, he looks like he could be John’s dad.

John’s dad would have had two kids, a son and a daughter—John and Harry. Likewise, the Cabbie has a son and a daughter.

Does army!John plus a son and a daughter immediately make a character a mirror for John’s father? Well, John is likely not the only military man in his family. There are theories that John’s father could also have been in the military. As @shinka lays out here, for instance, Major Barrymore in THoB shines light on the relationship John might have had with his father. John’s father, like Major Barrymore, could have been an ‘old-fashioned, traditionalist’, Thatcher-worshipping man, most likely hyper-masculine and homophobic. Incidentally, that is what the Cabbie supposedly represents.

In short, the Cabbie is also a mirror for John’s dad. Since the ‘military’ aspect of the Cabbie applies to both John and John’s father, it says a lot about John’s background, and the impact his father has on his life…

John’s childhood and military life—was John truly happy in the army?

So far in the show, we know very little about John’s past, and I doubt if it will ever become a major plot point. However, we are able to speculate based on what the Cabbie stands for, and whatever we have already seen in the show.

John’s father—like Major Barrymore, like what the Cabbie represents—is likely an old-fashioned, traditionalist, Thatcher-loving man, possibly also rather homophobic.

The Cabbie has a photo of his children as, well, children, but he seems too old to have children who are that young. He either hasn’t seen them since that age, or, on a more symbolic level, insists on only ever thinking of them as their younger selves.

John and Harry at that age would have been when they either have not realised their sexualities, or have not come out yet. John’s father would have refused to acknowledge the gender and sexualities that his kids come to identify with as they grow up.

The Cabbie (heteronormativity/homophobia) hunts and kills John mirrors, in the belief that what he is doing is good for his kids. We can imagine John’s father claiming the same thing—fiercely or even violently homophobic, John’s father could have, at one point, claimed that he needs to stop his children from being lesbian/bi for their own good. In doing so, he, like many homophobic parents, is driving John to the point of potential suicide.

The fandom has many theories on why John joined the army. Some popular theories include: Medical Corps cadetship covers tuition for a desperate closeted bi teen boy who has moved out of home, or wanting to feel useful while fulfilling his thirst for danger, etc. These are all possible reasons, but if John’s father was indeed in the army, then there may be one more: John may have joined the army to prove himself to his father.

As explained above, John’s father was probably in the military himself. He could even have been a Major, as @kinklock theorises here. We see that in the way John becomes more insecure in front of Major Reed in TSoT. He becomes ‘almost submissive, and seems to be trying to avoid eye contact’, hasty to reassert his title and achievements, and appears shot down when Reed dismisses him:

JOHN (pointing at his ID card): No, sir, I’m Captain John Watson, Fifth Northumberland Fusiliers-

REED: Retired. You could be a used car salesman now, for all I know. [x]

Wellingtongoose reckons, in their meta on John’s career, that John is originally in the Medical Corps, reached the non-combatant, purely administrative rank of Major, but then later switched to be trained as a combatant for whatever reason, which is how he can be both a doctor AND a soldier, and only a Captain at around age 35. His administrative rank as a Major would hold no power in the ‘gritty manly world’ of the Army, which adds a whole other layer to John’s self-esteem issue in relation to his father.

That is not to say, though, that John was unhappy in the army. He clearly takes great pride in his work and achievements. The army is also where John gets to embrace his sexuality to a fuller extent, and address his attraction to men.

For once, he has a pleasant relationship with a Major. Remember, however, his issues from his childhood remain unaddressed and unresolved. While he may have enjoyed his time in the army, he is still, consciously or not, living in the shadow of his father.

So John shoots the Cabbie…

When John is shot in Afghanistan, he is ripped from the work that he likes, the place that respects him, and the person that lets him be himself (to an extent at least). He is left financially and mentally struggling in London. At the start of ASiP, we have John, suicidal because he is forcibly removed from the one place where he enjoys himself. He would have felt like he has lost his purpose again, ridden with self-doubt, and feeling like somehow he has failed to prove himself.

Being invalided out of the army, however, does have one saving grace—one that we have seen time and again in fanfics:

If John has never been shot, he would never have met Sherlock.

Sherlock is key to John’s growth and recovery. He gives John the love and acceptance that has been missing from most of John’s life so far. Sherlock accepts John’s dual occupation (read: his bisexuality) right off the bat without reducing it just one part of it, and provides John with a non-civilian (read: non-heteronormative) lifestyle that John craves:

SHERLOCK: You’re a doctor. In fact you’re an Army doctor.

JOHN: Yes.

(He gets to his feet and turns towards Sherlock as he comes back into the room again.)

SHERLOCK: Any good?

JOHN: Very good.

SHERLOCK: Seen a lot of injuries, then; violent deaths.

JOHN: Mmm, yes.

SHERLOCK: Bit of trouble too, I bet.

JOHN (quietly): Of course, yes. Enough for a lifetime. Far too much.

SHERLOCK: Wanna see some more?

JOHN (fervently): Oh God, yes. [x]

When John shoots the Cabbie—in the same place where John himself is shot, he is symbolically killing the lingering oppression from his father that he has since internalised. Most importantly, John shoots the Cabbie to save Sherlock.

[x]

Sherlock lives means John Watson lives. By shooting the Cabbie—confronting and tackling ‘his doubts and his own crippling self-esteem issues’ [x], John can finally find happiness for himself, with Sherlock (the beginnings of which we have seen in TLD), and resolve his suicide crisis that we have been alerted to at the beginning of the episode.

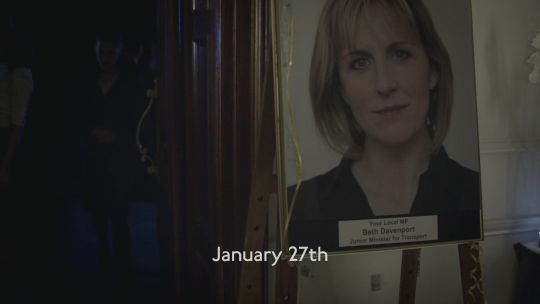

Bonus: Beth Davenport MP and S4 Car Crash Theory

After S4, as a branch of the Mind Bungalow Theory, @toxicsemicolon proposed the Car Crash Theory. You can read about it in detail in the linked meta, but simply put, the Car Crash theory suggests that John is involved in drink-driving accident, and while he is injured, whatever goes on in his head is what we see in The Final Problem.

Do we have another drink-driver on the show? Yes we do, and she is conveniently a John mirror: Beth Davenport MP, aka the Cabbie’s third victim, and ironically enough, the Junior Minister for Transport.

This MP has a drinking problem, and, from a conversation between her two aides, seems to have a tendency to drink-drive unless intervened:

JANUARY 27TH. At a public venue, a party is being held. A large poster showing a photograph of the guest of honour is labelled “Your local MP, Beth Davenport, Junior Minister for Transport.” As pounding dance music comes from inside the room, one of Beth’s aides walks out of the room and goes over to her male colleague who is standing at the bar. He looks at her in exasperation.

AIDE 1: Is she still dancing?

AIDE 2: Yeah, if you can call it that.

AIDE 1: Did you get the car keys off her?

AIDE 2 (showing him the keys): Got ’em out of her bag.

(The man smiles in satisfaction, then looks into the dance hall and frowns.)

AIDE 1: Where is she? [x]

Unfortunately, however, even though her aides prevented her from potentially killing herself and others through a drink-driving rampage, she still runs into the Cabbie and is murdered. It is also the report of her death that prompted John to make the blog post about the serial suicides (details in Part 2). If we follow the reading in this part of the meta, unless John’s demons from his childhood are tackled, even if his current problems (e.g. drinking) are resolved, he would still end up in the same dead end, literally.

Side note: if cars represent male virility, and John (and John mirrors) drink-drive…says a lot about John’s sex life, doesn’t it?

Part 2: ‘You can’t have serial suicides’ – media, chain suicides, and social problems

Part 3: ‘Who’d be a fan of Sherlock Holmes?’ – The biggest obstacle to Johnlock

Part 4: ‘I that am lost, oh who will find me?’ – John Watson’s Final Problem

106 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ms. Marvel #18 Review

spoilers spoilers spoilers spoilers spoilers spoilers spoilers spoilers spoilers

Guest artist, Francesco Gastón, joins writer, G. Willow Wilson, and colorist, Ian Herring, for this special stand-alone issue focusing on Bruno’s time as an exchange student in Wakanda. Full recap and review following the jump.

Bruno and Kamala had been the best of friends throughout most of their childhoods. As time went on, Bruno’s feelings for Kamala changed from friendship to romantic love. Kamala wasn’t able to return this kind of love but the two remained close friends. Then the second Super Hero Civil War occurred and events took place that would change Bruno’s life forever.

Captain Marvel’s special team of junior Carol Corps Cadets were tasked with utilizing the precognitions of the Inhuman known as Ulysses in order to prevent crimes before they occurred; and in her role as Ms. Marvel, Kamala was assigned to lead them. The Cadets proved overly enthusiastic and the power granted them to detain would-be criminals without due process quickly went to their heads. Kamala and Bruno’s classmate, Josh, was apprehended for a fire that Ulysses predicted he would set following a breakup with his girlfriend. Although Josh had once been a bully who teased Bruno mercilessly, Bruno could not sit idly by while Josh was detained without legal council. He decided to take matters into his own hands and built an explosive device that he intended to use to break Josh out. Unfortunately the device malfunctioned and detonated in Bruno’s hands, leaving him with severe injuries and paralysis to the right side of his body.

Bruno blamed Kamala for all that had happened. He saw her as responsible for the Carol Cadets abuse of power and although Kamala had quit the Carol Corps and even resigned her post as an Avenger, Bruno was still not willing to forgive her. He was offered a scholarship to study in the technically advanced nation of Wakanda and accepted it as a means of getting away from New Jersey and starting what was left of his life anew.

Whereas Bruno was a gifted student and well ahead of his class in Jersey City things are much different in Wakanda. Here in the Golden City of Birnin Zana, capital of Wakanda, he was quite behind in his studies compared to his peers and often feels alienated as a foreigner in a distant land. To make matters worse, his physical condition is continuing to deteriorate and it may not be long before he looses further functioning of his body. On top of it all, Bruno isn’t quite over his crush on Kamala. He may not be willing to forgive her, but that doesn’t seem to prevent him from still pining for her. Although interestingly, Bruno daydreams about her now seem to be more focused on Kamala in her Ms. Marvel guise rather than the girl she was when the two grew up together.

Bruno feels like a constant source of hardship and embarrassment to his roommate, Kwezi, and hence puts up with Kwezi’s frequent insults and demands that Bruno do his laundry. When Kwezi coerces Bruno’s aide in a complicated effort to impress a girl, Bruno feels obligated to go along.

Despite the antagonistic banter between Bruno and Kwezi, it appears clear that the two have become friends. For all of his eye-rolls and use of insulting nicknames, Kwezi is the one person who does’t look at Bruno with pity and treat him as a wounded charity case. And for this Bruno opts to accompany Kwezi on what turns out to more than just a stunt, but instead a rather risky venture wherein Kwezi has set out to pilfer a chunk of Wakanda’s invaluable vibranium ore.

Playing the role of hapless tourist, Bruno distracts the guards of the research center while Kwezi uses a special bracelet to gain entrance into the facility. It is quite painful for Bruno to be looked at with pity, to be seen as useless and broken. And yet he succeeds in distracting the guards. Once inside the research facility, the two ultimately discover the prize Kwezi has been searching for, a huge chuck of vibranium.

Kwezi only needs a small portion of the ore for his purposes and insists that he is only borrowing it so to attain proof of concept. He has Bruno use a laser cutting to carve off a small chunk of the ore while he reroutes the security programs to hide their presence. Bruno is right handed, yet his injury has forced him to have to learn to use his left hand. It’s been an extremely difficult process, made all the more arduous when people try to encourage him to just will his way through it. Yet he knows he must do so, he’ll never achieve the life he wishes for unless he is able to persevere through this hardship.

Bruno is ultimately able to carve the chuck off, catching the dislodged piece of vibranium with his good foot as it falls. Unfortunately, Kwezi is less successful with his own task and alarms sounds off. The two try to flee the scene only to come face to face with a legion of guards. Things become desperate; in the face of arrest and incarceration Kwezi and Bruno attempt to flee through a window. Bruno’s crutch slips on a piece of glass and he falls. Kwezi catches him by the good arm but can only hold on for so long. Dangling there, facing certain death, Bruno looks at his life from anew perspective. He knows that things are bound to get worse. His condition is permanent and likely to worsen as muscle atrophy will lead to neurological degeneration and possibly full body paralysis. Things will never be the same again yet despite it all he cannot give up; he wants to live.

Fortunately, The Black Panther swings in at the last moment, catching Bruno and grabbing Kwezi, jumping down to the safety of an adjacent building.

It turns out that Kwezi is actually The Black Panther’s nephew. Furthermore, his reasons for stealing the vibranium was not about impressing a girl but rather for a specialized harness meant to stabilize Bruno’s muscle atrophy and enable him enhanced functionality. Vibranium has special vibration-nullifying properties and Kwezi has designed a mechanism that would absorb kinetic friction and reenforce the neurological signals between Bruno’s brain and his paralyzed limbs. It would not afford Bruno a complete recovery but could vastly slow deterioration and afford greater mobility.

Bruno is all but dumbstruck that Kwezi has done this for him. He thought Kwezi hated him, yet now it turns out that he has risked everything to try to help him. Kwezi’s uncle, The Black Panther, is equally impressed by his nephew’s selflessness; so much so that he is willing to let this infraction slide. Kwezi and Bruno are allowed to keep the chunk of vibranium so to see if the project may prove a success. The tale ends with Bruno recalling a common Wakandan adage: ‘The Universe Is So Big It Has No Center; We Are The Center.’

A very nice and emotionally touching issue. Wilson and company just never miss a beat and Ms. Marvel continues to be the best all around comic on the stands. I certainly missed Kamala in the story, but it was cool seeing what Bruno has been up to and Kwezi proved to be a great character and a welcome new addition to the Ms. Marvel extended cast.

Bruno has had a really tough life. He was neglected throughout much of his childhood and had to work for everything, often relying on the kindness of Kamala’s family to help him out with basic needs. Despite his misfortunes, Bruno excelled in school and was on his way toward an Ivy League education and a bright future. Then it all fell apart and he seemingly lost everything.

It’s not really fair for Bruno to blame Kamala for what has happened to him. And the fact that he is still crushing on her puts his continued un-forgiveness toward her in something of a creepy light. Still, Bruno has good reason to be angry and sometimes that anger just need to be focused somewhere, anywhere.

He is facing a grim future. Injuries like he has sustained rarely get better and often get worse. He hates being looked at with pity and yet that pity has starting to set in as internalized and coming from himself. Bruno’s adventure with Kwezi has shaken him from this self-pity, reinvigorated his will to persevere through the hardship. And the kindness Kwezi has shown him highlights the fact that he doesn’t have to face this all on his own. Hopefully Kwezi’s gesture will motivate Bruno to finally forgive Kamala and allow their friendship to blossom anew.

Francesco Gastón does great work. The simple, cartoony style matches the tenor of the story quite nicely. There are some simply wonderful facial expressions that work like punchlines. Illustrating the advanced cityscape of Wakanda cannot be easy, but Gastón’s confident line does it justice and makes the fantastic Golden City feel like a real world local.

Once again, Ian Herring’s coloring is top notch. His work has become a lynchpin that maintains the titles’ sense of visual continuity with various illustrators penciling the books. Herring’s importance to the title cannot be overstated. Colorists rarely received the acclaim they deserve and Herring has been just as crucial to continual quality of Ms. Marvel as anyone else working on the book.

Another great issue despite the fact that Kamala herself wasn’t in it. Definitely recommended, but those with a tighter comic-buying budget can skip it in that it is a stand alone with a brand new arc starting with the next installment. Four out of Five Lockjaws

19 notes

·

View notes

Link

IN 1851, FOUR years after the inauguration of his anti-slavery newspaper The North Star, Frederick Douglass decided to reach out to the black man he would later say influenced him more than anyone else: James McCune Smith. In Douglass’s estimation, McCune Smith was one of the sharpest intellectuals of the era. Sometimes considered the most erudite African American prior to W. E. B. Du Bois, McCune Smith — largely forgotten despite his then-resplendent star — rose to prominence as a cosmopolitan who, upon being rejected from Columbia’s and Geneva’s medical schools in New York for being black, earned three degrees from the University of Glasgow in Scotland and thus became, upon his return to the United States, the first African-American university-trained physician to set up his own practice. He would go on to found the Radical Abolitionists and add to his fame through his criticism of Thomas Jefferson’s myopic views on race in Notes on the State of Virginia. Douglass wanted him to compose some sketches for the paper — rebranded that year simply as Frederick Douglass’ Paper after financial difficulties and a merger with the white abolitionist Gerrit Smith’s Liberty Party Paper — and McCune Smith responded with an extraordinary set of works titled “Heads of the Colored People, Done with a Whitewash Brush,” under the pseudonym “Communipaw.” Appearing between 1852 and 1854, the highly intertextual, at times even recondite articles each focused on some aspect of the black working class in New York, portraying vendors, fugitive slaves, interracial sexuality, and more. His evocations of black women’s sexuality, in particular, boldly defied the respectability politics of their time and made even Douglass — who preferred more sanitized, chaste portraits of African Americans — uneasy.

“Word paintings,” McCune Smith declared his installments, and they were just that, anticipating William J. Wilson’s famed 1859 “Afric-American Picture Gallery,” in which Wilson, through text, “painted” ennobling portraits of black subjects, like Phillis Wheatley and Toussaint L’Ouverture. That same year, another series of groundbreaking word paintings of black Americans (and also of the African diaspora more broadly) appeared in the brief-lived Anglo-African Magazine: “Fancy Sketches,” by Jane Rustic, whose real name was Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. Like McCune Smith, Rustic remains neglected today but was a prominent intellectual of her era — a black woman who lectured across the country for abolitionism, published prolifically (including poems and serialized novels), and advocated for feminism.

These three series are mentioned in Nafissa Thompson-Spires’s debut story collection, Heads of the Colored People, which can be read — even from its title — as a new millennium’s idiosyncratic version of McCune Smith’s installments. Thompson-Spires’s stories owe many additional debts — a number of which the author acknowledges in an endnote and even in a supplied bibliography — to a wide range of texts, from popular Japanese anime to Percival Everett to Ralph Ellison. Clever, cruel, hilarious, heartbreaking, and at times simply ingenious, Thompson-Spires’s experimental collection poses a simple, yet obviously not-simple, question: what does it mean to be a black American in this day and age?

¤

Thompson-Spires’s metafictional satires, oriented around questions of blackness, join a particular tradition of African-American fiction, recalling the sardonic absurdism of Everett’s Erasure and Paul Beatty’s The Sellout, among others. The opening story’s incessant hedging about language — meant, in part, to parody, ad nauseam, the almost paranoiac way that our language about identity tends to be policed — also echoes the seemingly half-serious, half-satirical narration of Danzy Senna’s recent novel, New People, in which a light-skinned part-black woman is driven near to madness by her obsession over not appearing “black enough.” Not all of Thompson-Spires’s stories are overtly satirical, and they become progressively more serious as the collection progresses, but a thread of outrageous, glaring self-awareness runs through the collection, granting even many of the more severe tales a tone of dark comedy.

The collection’s quick nod to Ellison’s Invisible Man belies its debt, too, to that novel, as these characters, like Ellison’s narrator, are tormented at once by being too visible and not visible enough, though these characters often wish their blackness was more visible. Unlike Ellison’s narrator, some of these characters use social media, and the addictive cost of visibility there, too, becomes a relevant leitmotif. Many exist in liminal states of blackness: black, but not, but inescapably black, but, but. The opening story, which shares part of its name with McCune Smith’s series, begins with a deadpan assurance to readers that a black otaku named Riley who “wore blue contact lenses and bleached his hair” didn’t do any of this out of

any kind of self-hatred thing. He’d read The Bluest Eye and Invisible Man in school and even picked up Disgruntled at a book fair. […] He was not self-hating; he was even listening to Drake — though you could make it Fetty Wap if his appreciation of trap music changes something for you, because all that’s relevant here is that he wasn’t against the music of “his people.”

In “The Subject of Consumption,” Ryan, a black fruitarian, ponders the way other African Americans might frown upon his marrying a white woman, Lisbeth, out of the assumption that he did not care for women of his own race and merely wanted “light-skinned babies.” The blackness of these characters is simultaneously stable and always in question.